Divulgazeral

Pollution in the Odiel Marshes: a trap for the black-necked grebe

The migratory population of black-necked grebe in the Odiel Marshes is exposed to potentially toxic levels of metal pollution during its stay in the coastal wetland for the purpose of moulting

The Odiel Marshes, which are located in the mouth of the Tinto and Odiel rivers, in the south of the province of Huelva (Spain), are one of the most important coastal wetlands in the Iberian Peninsula owing to their high ecological, socioeconomic and cultural value. At this point of Spanish geography, the encounter between freshwaters from Sierra de Aracena and the marine waters from the Atlantic Ocean have created a genuine mosaic of landscapes in which water channels, lagoons, salt ponds, islands and forests combine to form an authentic paradise for biodiversity, and particularly for a host of waterbirds. It is considered to be of such importance, that the Odiel Marshes have been declared a Natural Park, a Site of Community Interest, a Special Protection Area for Birds, a Wetland of International Importance and a Natural Reserve of the Biosphere.

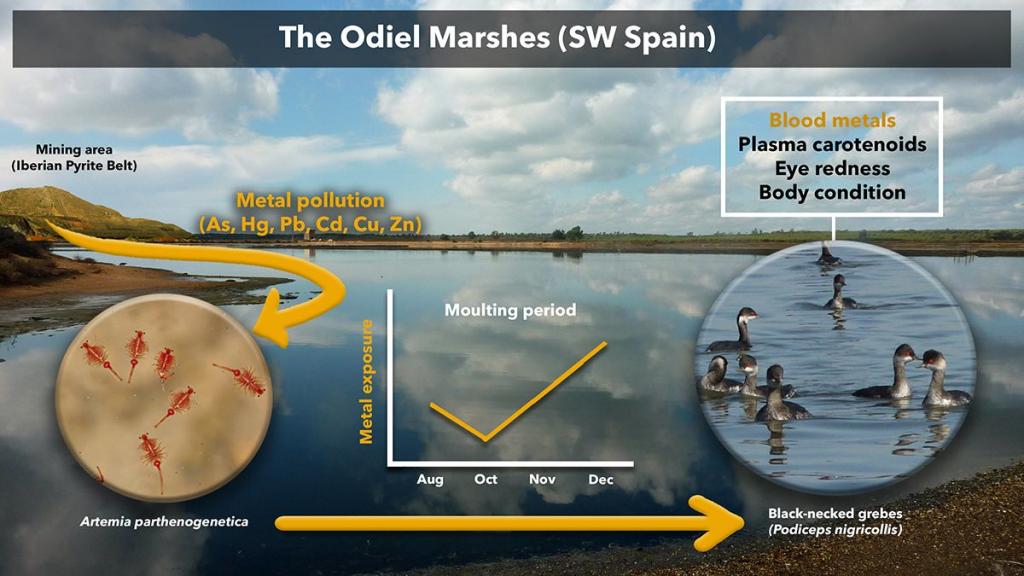

Despite its high ecological value and level of protection, the conservation of this rich ecosystem is not free from threats. Upstream, in the north of the province of Huelva, the watersheds of the Tinto and Odiel rivers receive large amounts of metals from the abundant mining residues that have been abandoned in the Iberian Pyrite Belt, a globally important metallogenic province historically subjected to intense mining activities. These metals are dragged into the waters and sediments in the marshes, where they cause a severe problem as regards metal pollution that is aggravated by additional pollution from the large industrial chemical complex in nearby Huelva. Of the metals causing this environmental impact we can highlight arsenic (As), mercury (Hg), lead (Pb) and cadmium (Cd), which are known because of their high toxicity and persistence; and copper (Cu) and zinc (Zn), which are essential elements –living organisms need them to live– but become toxic in excess.

Metal pollution in the Odiel Marshes implies the following risks: the wildlife inhabiting this ecosystem being exposed to potentially toxic metals, animals accumulating metals in their tissues and metals being transferred through trophic chains and/or wildlife suffering negative health effects, thus threatening the survival of wild populations. This sequence of risks is of particular concern when it involves a wildlife species like the black-necked grebe (Podiceps nigricollis), a small waterbird labeled as “Near Threatened” by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) that is particularly vulnerable to environmental degradation.

Every year, from mid-summer to early winter, about 10,000 grebes from breeding areas across the continent reach the hypersaline waters of the Odiel Marshes for the purpose of moulting, forming one of the largest congregations of the species in southeast Europe. Grebes do not live permanently in this bird sanctuary but migrate to it after reproduction to renew their feathers and to recover energy before flying to wintering areas. Interestingly, grebes replace all their wing feathers simultaneously, which renders them completely flightless for a period, signifying that they need to seek places that will provide them with the basic necessities for survival without the immediate need to fly.

The Odiel Marshes are an ideal place for grebes to moult, since they provide extensive bodies of water in which grebes can concentrate in large flocks, safe from predators. The marshes also guarantee a nutritive and predictable food item to meet their energy and nutritional demands for moulting and for the accumulation of fat reserves –which in the world of wildlife means getting fat– before moving to wintering areas: the brine shrimp (Artemia parthenogenetica), a tiny crustacean that is highly abundant in the salt waters of the marshes during the months that grebes inhabit them. The problem is that, owing to metal pollution in the aquatic environment and the ability of shrimps to take up and assimilate metals, grebes might be exposed to high levels of pollutants, which would involve a conservation risk, thus converting the Odiel Marshes into an ecological trap for the migratory population of the species.

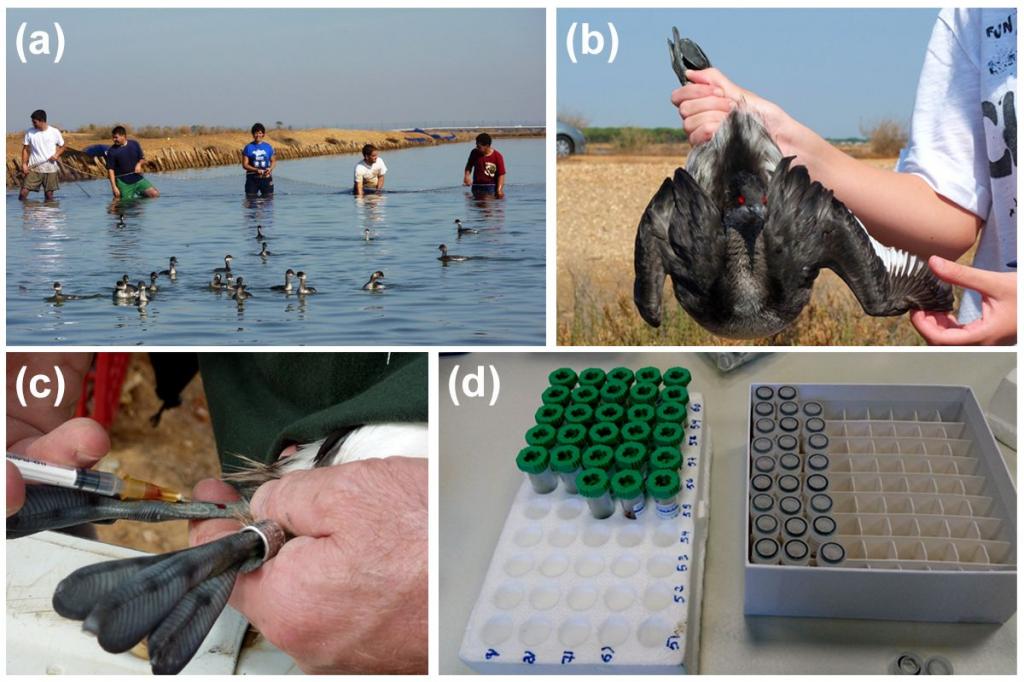

Research led by the Wildlife Toxicology Group of the Instituto de Investigación en Recursos Cinegéticos (IREC – CSIC, UCLM, JCCM) and the Department of Wetland Ecology of the Estación Biológica de Doñana (EBD – CSIC), in which scientists from the Instituto de la Grasa (IG – CSIC) and the University of the Highlands and Islands (United Kingdom) also participated, has enabled us to evaluate the degree of exposure of grebes to metal pollution in the Odiel Marshes during the period that they spend there for their critical life-history event of moulting. Moreover, we have studied whether this exposure has the potential to compromise grebes’ health and survival, and the role of brine shrimps as vectors for the transfer of metals to grebes. This was done by studying different biomarkers, which are –in the context of the present work– “measurements” of certain physical, chemical or biological parameters that indicate whether grebes are exposed to worrying levels of environmental pollutants (biomarkers of exposure) and/or whether this exposure is linked to negative health effects (biomarkers of effect).

As expected, grebes are not exempt from the problem of metal pollution in the Odiel Marshes. The levels of metals detected in their blood (biomarker of exposure) are high for As and Zn in comparison to the toxicity thresholds. Moreover, 12% of grebes had much higher levels of Hg than those considered to be normal for a bird species like the black-necked grebe. Brine shrimps also accumulate levels of As, Pb, Cu and Zn between 3 to 12-fold higher than those expected for shrimps inhabiting unpolluted waters. If we add to this the fact that the grebes’ exposure to metal pollution changes over the studied period following a temporal pattern similar to that of the availability of shrimps (which are the main food item for grebes during their stay in the marshes), then we can affirm that grebes in the Odiel Marshes are exposed to high levels of metal pollution, and that the trophic transfer through the consumption of shrimps plays a key role in the levels and patterns of exposure.

The grebes’ exposure to metal pollution was linked to changes in plasma carotenoids, the intensity of the eye colour and body condition (biomarkers of effect). Carotenoids are organic pigments that have to be acquired through diet and that play key roles in antioxidant and immunological functions. Moreover, they influence social and sexual signalling in birds through the production of colour traits, such as eye redness in grebes, signifying that the more intense is the redness, the better is the reproductive quality and/or the fitness of its bearer. The positive relationships that we have found between exposure to As and Hg and plasma carotenoids in grebes, together with the temporal variation of the later, indicate that grebes absorb carotenoids and metals simultaneously through the consumption of shrimps. Nonetheless, exposure to As was negatively related to eye redness, which reveals that part of the carotenoids that should be used for carotenoid-based colouration are used to counteract or ameliorate the negative effects of metals on other physiological functions. Furthermore, the grebes’ body condition was positively related to exposure to As, which make sense as grebes gain weight through the consumption of shrimps, which are also their main source of exposure to As.

It is clear that grebes in the Odiel Marshes are exposed to sufficiently high levels of metal pollution to cause health risks, at least during the critical period of their life cycle represented by moulting. The results from this work highlight not only that favouring biodiversity conservation in the Odiel Marshes involves the need to reduce metal pollution, but also the complexity of ecotoxicological risk assessments associated with polluting anthropogenic activities. The ecological interactions among species, the physiological status of animals and gender-related differences, the availability of food resources, interannual variations in environmental contamination and the adaptive adjustments of animals to the environment in which they live, are just some of the factors that should not be overlooked when using waterbird species like the black-necked grebe as bioindicators to evaluate the conservation status of an ecosystem.

The scientific publication of this research is available at:

- Rodríguez-Estival, J., Sánchez, M. I., Ramo, C., Varo, N., Amat, J. A., Garrido-Fernández, J., Hornero-Méndez, D., Ortiz-Santaliestra, M. E., Taggart, M. A., Martinez-Haro, M., Green, A. J., Mateo, R. 2019. Exposure of black-necked grebes (Podiceps nigricollis) to metal pollution during the moulting period in the Odiel Marshes, Southwest Spain. Chemosphere 216, 774-784.

If you are interested in discovering more about the role of ecological interactions among grebes, shrimps and the parasite that they transmit to grebes, in the scenario created by metal pollution in the Odiel Marshes, you may wish to read the following informative article [In Spanish]:

- Sánchez, M. I., Mateo, R., Varo, N., Rodríguez-Estival, J., Hornero-Méndez, D., Garrido-Fernández, J. 2018. Black-necked grebes against pollution: The importance of ecological interactions. Quercus 386, 12-18.

Are you interested in Environmental Sciences and Science communication?

Subscribe to our Newsletter at the end of our website!

Are you a scientist in the field of Environmental Sciences and would like to disseminate the results of your work in Divulgazeral?

Contact us in info@azeral.es!